On this date in 1934...

|

| Sedalia Democrat |

Two gunmen fatally shot John Lazia, underworld-connected political boss of Kansas City's north side "Little Italy," July 10, 1934, as he stepped out of a car in front of his apartment building.

Lazia and his wife had spent the evening of Monday, July 9, with their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Carrollo, in the Lake Lotawana area, where the Lazias had a summer home. They returned to Kansas City in the early morning hours of July 10 in an automobile driven by Carrollo. Mrs. Lazia was seated in the front, beside Carrollo, while Lazia and Carollo's wife sat in the rear.

They pulled into the semi-circular driveway of the Park Central apartment building, 300 East Armour Boulevard, where the Lazias lived. When the car stopped under the building's front entrance canopy, John Lazia emerged from a rear seat and began to open the front door to help his wife from the car. At that moment, two gunmen opened fire on Lazia with a machine gun and a shotgun.

|

| Mrs. Lazia |

As Lazia fell wounded, he called out, "I'm shot. Get Marie out of here. Step on it, Charlie!"

Carrollo did as he was instructed. The gunmen advanced and fired more shots into Lazia's body. They then ran off into an alley beside the apartment building, climbed into a waiting automobile and escaped.

Lazia was rushed to St. Joseph Hospital (then about two miles away on East Linwood Boulevard). Doctors tended to his wounds - he had been struck by slugs in his chest, shoulder, head, back and arms - and administered three blood transfusions. They were unable to save Lazia. He died at the hospital at just after two o'clock that afternoon.

Lazia claimed not to know who shot him. In his final moments, he told Dr. D.M. Nigro, "I don't know why they did it. I'm a friend to everybody. I don't know why they did this to me."

Newspapers noted that Lazia was an important lieutenant in the political machine of Kansas City Democratic boss Thomas J. Pendergast. It was said that Lazia personally controlled 30,000 votes in the city. The killing brought considerable negative attention to the Pendergast machine. It was the second time that Lazia had damaged the organization. The machine's connections to the region's underworld had been exposed through Lazia's trial for income tax evasion five months earlier. At the time he was murdered, Lazia was free on bond awaiting an appeal of failure to file convictions that resulted in a one-year prison sentence, five years' probation and a fine.

|

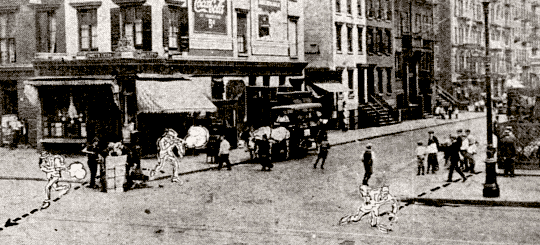

| St. Louis Star and Times shows location of victim and gunmen |

Investigation goes nowhere

Otto P. Higgins, director of the local police force, took personal charge of the Lazia murder investigation. Joe Lusco, a north side political rival of Lazia, was immediately brought in for questioning. Police also rounded up more than twenty of Lusco's followers.

|

| Lusco |

Lusco was reputed to be part of Casmir Welch's political organization, which battled the Pendergast machine. A feud between the Lusco and Lazia factions had already claimed a number of lives, including that of Ferris Anthon, believed killed by Lazia-affiliated gunmen in the summer of 1933.

Lusco, however, insisted that any problems he ever had with Lazia had been resolved long ago. Lusco told investigators that he and Lazia were the closest of friends. Without evidence against the rival faction, police were forced to release Lusco and his men.

There was some suspicion that Lazia was targeted due to the arrests of two men for the killing of bank messenger Webster Kemner during a robbery earlier in the year. Sam DeCaro and Charles Taibi were charged with the Kemner killing. DeCaro was quickly tried, convicted and sentenced to life in prison. Taibi was awaiting trial at the time of Lazia's murder. There were rumors that Lazia provided information to police that linked DeCaro and Taibi to the slaying of Kemner.

|

| Lazia |

Eventually, the local authorities suggested that Lazia was killed by gangsters from outside the region. Lazia, they claimed, had enraged distant gang bosses by refusing to allow their men to operate within the Kansas City area.

In the fall of 1934, federal agents found interesting connections between the killing of John Lazia and the Union Station Massacre in Kansas City a year earlier. Kansas City gangster James LaCapra told authorities that Lazia aided gangsters "Pretty Boy" Floyd, Adam Richetti and Verne Miller in their failed but bloody attempt to free Frank Nash from federal custody. Agents also discovered that markings on machine gun bullets used in the massacre were a match for bullets recovered at the scene of Lazia's murder, suggesting that the same machine gun was used in both incidents. Authorities felt this was an indication that Lazia was killed by former allies rather than by known enemies.

Stand-up guy?

|

| St. Louis Post-Dispatch |

Police and press seemed not to consider that Lazia's recent income tax case had anything to do with his killing, though testimony in that case revealed to press, police and public the connections between political bosses and underworld bosses, the amount of money generated through local gambling rackets and the specific amounts that had been paid to county law enforcement personnel to ensure protection of those rackets. In fighting the government's case, Lazia went to the witness stand, named business partners and described financial transactions. And his fight did not end with his conviction.

When the jury returned a generous verdict, finding him guilty only of misdemeanor failing to file returns for two years and acquitting him of felony tax evasion, Lazia did not act in the way expected of a "stand-up guy." He went to the press and stated, "I'm a victim of prejudice. I feel I've been convicted on charges that never would have been placed against most businessmen."

Though a federal judge in spring 1934 overruled a request for a new trial, Lazia pressed ahead with an appeal, further increasing the exposure of his underworld colleagues. One month before his murder, Lazia learned that the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Omaha, Nebraska, would hear his appeal in October.

Saying goodbye

Lazia's remains were placed in a casket reportedly valued at $5,000. Some sources described the casket as silver-plated bronze, others as silver-lined copper. A wake was held at the home of Lazia's sister, and an estimated 10,000 people visited through the night.

|

| St. Louis Star and Times shows funeral procession |

On the morning of July 13, about 1,000 people were still crowded around the sister's home as the funeral procession to Holy Rosary Church commenced. More thousands lined the route to the church. Thomas J. Pendergast participated in the sendoff, along with former north side political boss Michael Ross and City Manager H.F. McElroy. The procession included 120 cars and was followed by four trucks filled with floral offerings.

|

| Lazia |

The most noteworthy floral piece was a large wheel and axle with an obviously missing second wheel. That was sent by Pendergast. Newspapers called attention to the fact that flowers had been sent from individuals in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans and other U.S. cities. Even Joe Lusco sent flowers.

Following the funeral Mass, Lazia's remains were taken to St. Mary's Cemetery to be buried next to the graves of his father and mother.

Though John Lazia was dead and buried, the U.S. Bureau of Internal Revenue was not quite done with him. About a week after the funeral, Collector of Internal Revenue Dan M. Nee filed a lien of $62,280.01 against the Lazia estate, including property owned by Lazia's widow. The government argued that Lazia failed to pay $48,847.76 in owed taxes for the years 1927 through 1930 and also owed interest and fines totaling $13,432.25.

Sources:

- "John Lazia, Kansas City politician, goes to trial," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 5, 1934, p. 4.

- "Gambling den 'fixing' bared in Lazia trial," St. Louis Star and Times, Feb. 6, 1934, p. 1.

- "Says protection of Lazia's resort cost $500 a week," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 7, 1934, p. 1.

- "Maze of tax data piled up at Lazia trial," St. Louis Star and Times, Feb. 8, 1934, p. 1.

- "Lazia deposits put at $153,871 for two years," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 9, 1934, p. 2.

- "Lazia had money; was it taxable? Is issue at trial," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 10, 1934, p. 3.

- "Move by Lazia's lawyers to halt tax evasion trial," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 11, 1934, p. 16.

- "Lazias lived on $150 a month, wife testifies," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 12, 1934, p. 3.

- "Prosecutor asks for 'horse sense" in Lazia verdict," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 13, 1934, p. 6.

- "Lazia convicted on two counts in income tax case," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 14, 1934, p. 1.

- "Lazia is guilty on two charges," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, Feb. 14, 1934, p. 1.

- "Lazia is sentenced by Judge Otis," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, Feb. 28, 1934, p. 7.

- "John Lazia gets year in jail on U.S. tax charge," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 28, 1934, p. 3.

- "A new trial for Lazia is probable," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, April 9, 1934, p. 6.

- "Lazia hearing Saturday," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, April 10, 1934, p. 2.

- "John Lazia denied retrial," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 14, 1934, p. 2.

- "Lazia appeal will be argued in Omaha," Jefferson City MO Post-Tribune, June 1, 1934, p. 2.

- "John Lazia dies after being shot by two gunmen," Sedalia MO Democrat, July 10, 1934, p. 1.

- "John Lazia shot down by 2 unidentified gunmen today," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, July 10, 1934, p. 1.

- "Machine-gunners shoot John Lazia, Pendergast's aid," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10, 1934, p. 1.

- "Politicians are dazed by death of Johnny Lazia," Jefferson City MO Post-Tribune, July 11, 1934, p. 3.

- "A Chillicothe young man to aid of wounded man," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, July 11, 1934, p. 1.

- "Great throng files past John Lazia bier," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 12, 1934, p. 3.

- "Italians honor Lazia, lies in $5,000 casket," Jefferson City MO Post-Tribune, July 12, 1934, p. 10.

- "The Lazia funeral to cost $40,000," Chillicothe MO Constitution-Tribune, July 12, 1923, p. 1.

- "Thousands line funeral route of John Lazia," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 13, 1934, p. 1.

- "Government files $62,280 lien on John Lazia estate," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 21, 1934, p. 3B.

- "John Lazia linked with massacre of 5 at Kansas City," St. Louis Star and Times, Oct. 11, 1934, p. 3.